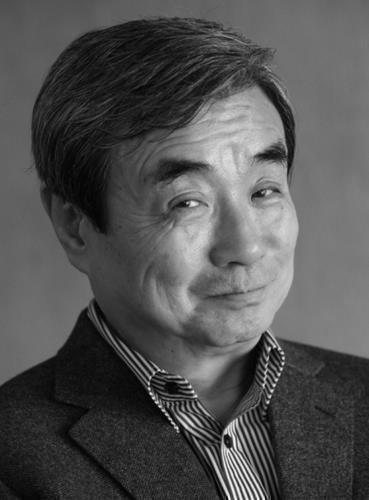

This happened over 20 years ago.

At a gathering with many juniors, a young woman who had just graduated from graduate school and was working at an architectural firm said:

"It’s an honor to finally meet Professor Kim Won, whom I’ve always respected. But I’ve heard some people speak ill of you. I was especially surprised when I heard it from a senior who used to work at Gwangjang long ago."

Someone next to her tried to stop her, saying, "Hey, that’s pretty bold."

For a moment, the room fell silent, and everyone turned to look at me. Seeing the young woman looking embarrassed, I tried to brush it off lightly.

"Oh, of course, it would be a mistake to think that everyone in the world likes me. And especially the people who worked with me—most of them probably got scolded more than they got praised, so it’s even more understandable."

For several days after that, her words kept ringing in my ears.

Even though I had answered that way at the time, it made me wonder: are there more people who like me, or more who hate me? To be honest, I had never really thought about it before. I simply avoided people I disliked and surrounded myself with those who liked me, so it was natural that I had never given it much thought.

But thinking carefully, there’s no reason to believe that there aren't people who dislike or even hate me—maybe even some who grind their teeth at the very thought of me.

The first time I felt this was back in elementary school. As the class president, I had to line up my classmates, keep them quiet, and make sure they studied during self-study periods. There was always one student who caused trouble and refused to listen.

At the time, I thought:

"Ah, this kid hates me."

I don't clearly remember how I handled it, but I think I just ignored it.

"The teacher will understand."

That must have been my mindset.

Just as I expected, the student got a severe scolding from the teacher, and only then did he stop his mischief.

And of course, I probably consoled myself by thinking, "See? Serves him right." But his resentment must have only grown stronger.

After that, I started thinking about other instances when I might have provoked someone’s dislike, and strangely, I found it amusing.

I remembered something that surprised me during my university days. A friend once told me, "I hate all the kids who went to Kyunggi High School."

When I asked why, he said he had taken the entrance exam for Kyunggi but failed, and ever since then, he had developed that grudge.

I didn’t know whether to console him or try to change his mind, so I just ended it by saying, "You’re an idiot."

Luckily, we were old enough by then to laugh it off, but I'm sure that feeling didn’t just disappear from his mind.

What About the Workplace?

Naturally, when I was recognized, trusted, and favored by my superiors for my work, there must have been far greater resentment around me than the joy I felt. But I was oblivious to that and simply took it for granted.

Thinking back, I shudder at how clueless I must have seemed to others. It’s shameful that I didn’t realize how my small happiness could bring immense despair and disappointment to others.

Even worse, I can only imagine how many people I must have hurt with my writings, where I forced my opinions onto others in the name of criticism.

What made me think I knew so much? How many buildings had I even designed? And yet, I harshly dissected my mentors, seniors, colleagues, and juniors alike.

I even heard people say, "Young man, watch your words. Do you think knives don’t cut into other people’s bellies?"

How deep must their resentment have been to say something so harsh?

Yet, in my arrogance, I "confidently" replied:

"Write a rebuttal. I’ll make sure it gets published next month."

At that time, I was truly an immature and thoughtless person.

And after I opened my own firm and started working independently, who knows how many more people I have hurt? Just thinking about it fills me with fear.

I Always Thought I Was Right

I always believed that I was right. From that perspective, anything that was not right was simply categorized as wrong and dismissed.

To me, concepts like justice and truth were sorted into a black-and-white logic, a strict dichotomy. At the office, I believed that juniors who couldn’t do their jobs should be let go.

At construction sites, I insisted that incompetent carpenters or plasterers be fired immediately. Construction companies that won bids with unrealistically low estimates and then dragged out the work seemed to me like the embodiment of injustice. If a client refused to accept my ideas, I would argue with them—no matter who they were—and I would never meet them again.

A good example of this is found in the testimony of the late painter Kim Jeom-seon (1946–2009). In her later years, we used to meet frequently, and every time, she would tease me by bringing up the story of our first encounter.

She said she first met me in the late 1970s when I had an office in Sagan-dong. At the time, she happened to visit with Park Yeo-sook, the head of Park Yeo-sook Gallery.

Apparently, we talked for an hour or two, and the impression she took away from that meeting was:

"Could there be anyone in the world as arrogant, haughty, and self-important as this man?"

She found me unbearably unpleasant.

To be honest, I don’t remember that incident well. I had always believed that I gave off a gentle impression, that I spoke in a soft, quiet voice, and that I behaved with humility. So hearing Kim Jeom-seon’s recollection was truly unexpected.

I prided myself on speaking the truth and doing the right thing, even if it meant being disliked.

After all, Jesus was killed by his own people, and Lincoln and Gandhi were assassinated for advocating righteousness. So I believed that the more I pursued what I thought was right, the more I would be hated.

But is that really true?

There was a time when I won consecutive awards from the Architectural Association. Then, I heard that someone had said, “Why should one person keep winning Association awards? That’s not right. Let’s stop giving them to Kim Won.”

I laughed at that.

But there’s no helping the fact that people develop dislike for others. Sometimes people are hated for being too competent, or for speaking too bluntly. Excelling too much naturally makes one a target of resentment. Even those who never make mistakes and leave no room for error can be disliked.

For a long time, I loudly proclaimed that many things in the world were going wrong. To others, it must have sounded like I was saying, “I’m right, and everyone else is wrong.”

In other words, I had taken a dogmatic stance toward society for a very long time.

During the era of my mentor, the architect Kim Swoo-geun, that kind of attitude was sometimes necessary. I, too, was deeply influenced by it.

But how do I feel now?

I sense that I have changed somewhat. Now, the idea of being dogmatic seems absurd. Instead of loudly proclaiming “This is wrong!”, I quietly think to myself, “That’s not quite right.”

It’s not just because I fear being disliked. It’s probably because I’ve grown older. Or maybe I’ve mellowed a bit.

One year, at a year-end gathering, an older colleague said:

"Sir, I hear you've become much more lenient with your employees these days."

I replied, “Really? I hadn’t noticed. But if that’s how it seems, then that’s a good thing.”

Does that mean that when employees leave these days, they resent me less than before? In any case, it’s true that people often feel very differently when they leave a job than when they first join.

Hope and despair, respect and contempt, love and hatred—they all intertwine.

To navigate these emotions smoothly, one should start without too many expectations. It all comes down to excessive desire on both sides.

Ultimately, in every situation, all love and hatred stem from my own faults.

If someone dislikes me, it is entirely my responsibility.

Because depending on how I acted, I could have prevented them from feeling that way in the first place.

(C) Yonhap News Agency. All Rights Reserved

![[풀영상] 2025 MBC 방송연예대상 레드카펫|유재석·전현무·기안84·김연경·세븐틴 부승관·박지현·제베원(ZB1) 규빈·투어스(TWS) 도훈·주우재·하하 외](/news/data/20251229/p179586605817354_616_h.jpg)