*Editor’s note: K-VIBE invites experts from various K-culture sectors to share their extraordinary discovery about the Korean culture.

Choi Man-soon's Medicinal K-Food: The True Meaning of "Rice Is the Best Medicine"

By Choi Man-soon, Food Columnist and Director of the Korea Traditional Medicine Food Research Institute

From ancient times, Korea has been known for its abundant mountains, where the clear waters of deep valleys and natural springs were regarded as high-quality "Gamcheonsu," or sweet spring water. Many people referred to these waters as "yak-su" (medicinal water) and used them as beverages.

In addition to consuming natural spring water, Koreans developed various methods of creating drinks by boiling grains, medicinal herbs, edible fruits, flowers, leaves, and honey-soaked ingredients.

Korean traditional beverages, in particular, focused on health benefits, such as preventing illnesses and helping people endure the heat of summer and the cold of winter.

The preparation methods varied depending on the type and form of the beverage. Historical records classify them into different categories, including tea, decoctions, fermented grain drinks, grain-based drinks like Sikhye, rice water, and fruit punches.

|

| ▲ This file photo shows Andong sikhye. (Yonhap) |

◇ Traditional Beverages Made with Natural Ingredients

Korean traditional drinks are made from medicinal herbs, flowers, and fruits obtained from nature, and they come in a wide variety.

The ancient Chinese text Ben Cao Ji Jing Zhu by Tao Hongjing states that "the Schisandra produced in Goryeo is of the highest quality, with plump, sour, and sweet berries," indicating that these fruits were even exported.

Historical records such as the Annals of the Joseon Dynasty mention that King Yeongjo enjoyed Omija tea to quench his thirst, while The Diaries of the Royal Secretariat record that King Injo provided his sick officials with ginseng tea to restore their energy and Omija tea to relieve their thirst.

Among Korea’s traditional beverages, the most well-known are Sujeonggwa and Sikhye. Sujeonggwa is made by boiling ginger and cinnamon and adding dried persimmons and pine nuts. The book Sanlim Gyeongje (산림경제) by Hong Man-seon documents various types of Sujeonggwa, including versions made with plum blossoms, yuzu, hawthorn berries, angelica root, and black plums.

All these variations involved grinding ingredients into powder, boiling them, and mixing them with honey and pine nuts, collectively referred to as Sujeonggwa. Meanwhile, Siui Jeonseo records a variety of fruit punches consumed in royal courts, including rose punch, azalea punch, water shield punch, pear punch, cherry punch, raspberry punch, balsam punch, and barley water punch.

Because most ingredients for these traditional beverages were relatively easy to obtain and had long shelf lives, they became essential parts of daily life. They were consumed as refreshments, served during festive occasions, and enjoyed after meals.

Traditional Korean beverages were not only aromatic but also used beneficial medicinal ingredients combined with seasonal, fresh produce. One of the most commonly used ingredients was malted barley (맥아), which has a sweet taste and warm nature. It was believed to aid digestion, relieve bloating, and improve appetite.

Sikhye, made using malt, was particularly valued as a post-meal digestive aid. This made it a perfect drink for holidays and celebrations, where people indulged in feasts.

|

| ▲ Park Young-jun harvests omija at an open-field omija farm at 600m above sea level in Baegun-ri, Baekjeon-myeon, Hamyang County, South Gyeongsang Province, on September 9, 2024, in this photo provided by Hamyang County. (PHOTO NOT FOR SALE) (Yonhap) |

◇ Memories of Sikhye Made by Mother

When I was a child, the sweet aroma filling our kitchen signaled that it was Sikhye-making day.

That scent, infused with warmth, enveloped me like a comforting embrace, while my mother’s hands, moving diligently in front of the hearth, worked a kind of magic.

She would carefully wipe the lid of the large cauldron with a cloth, gauging the temperature, and patiently extract the essence of malt. The kitchen would then settle into a quiet rhythm of waiting. I sat beside her, keeping her company as she shared stories about Sikhye.

"Son, when making Sikhye, we add pine needles. They act as a natural preservative, preventing spoilage, and they strengthen the digestive system."

She poured malt extract into a large wooden bowl and let it soak for about an hour before rubbing the grains vigorously to extract the milky white liquid, which was then strained through a sieve. The remaining solids were soaked and strained once more to ensure no essence was wasted.

After allowing the liquid to settle overnight, she would carefully filter it again if it appeared cloudy, explaining that a clear Sikhye broth was key to its quality.

Once the preparations were complete, she poured the malt liquid into a large cauldron and started a fire. Meanwhile, she cooked glutinous rice separately in a small pot, adding just enough water to make firm, chewy grains. After spreading the rice out on a tray to cool, she mixed it into the malt liquid and let it simmer for 10 minutes.

Then, she lowered the fire, using embers and charcoal to maintain a consistent temperature of around 60°C for six hours, allowing the fermentation process to unfold.

"If you leave it too long, the rice grains will dissolve. If it's too short, the deep sweetness won’t develop. Controlling the fire is key."

She remained by the cauldron, watching over it with unwavering patience. When she finally lifted the lid and saw the rice grains floating, a gentle smile spread across her face.

"Look, the rice grains are floating—it's done."

Holding my breath, I peered into the pot. Like tiny stars rising in the night sky, the grains drifted to the surface. At that moment, I could feel the Sikhye was complete.

She then added pine needles wrapped in a hemp cloth along with a touch of Shinhwadang (신화당, a traditional sweetener) and let it boil for 10 more minutes. Once cooled, she strained out the pine needles, separated the floating rice, and poured the Sikhye into small earthen jars.

The kitchen was filled with a deep, soothing sweetness. My mother ladled some Sikhye into a small bowl and placed it in my hands.

I blew gently on it and took a sip. The soft, sweet taste spread through my mouth—it was the taste of love, crafted with time and care.

Years have passed, and now I make Sikhye following my mother’s method. As I carefully extract the malt and cook the rice, waiting by the warm rice cooker, I recall her gentle hands.

Surrounded by that familiar sweet scent, I find myself transported back to my childhood.

There, my mother was always present, offering unwavering love.

Each sip of Sikhye brings back that warmth, and suddenly, I miss her dearly.

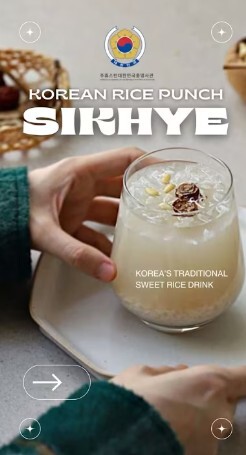

◇ Sikhye Through the Lens of The Art of War

In "The Art of War," the Nine Grounds chapter emphasizes the importance of understanding terrain and soldier psychology when crafting strategies. Applying this to traditional Korean beverages offers insight into their survival in modern times.

The first concept is Scattered Ground, where troops are easily dispersed. This resembles how traditional beverages, once widely consumed, have lost ground to coffee and carbonated drinks. Young generations now encounter these drinks only on special occasions, leading to weakened connections—just like scattered troops struggling to form a strong front.

To revive traditional beverages, they must be reintegrated into daily life. This could be done by modernizing café menus, redesigning packaging to appeal to younger consumers, or creating new trendy variations.

The second concept is Light Ground, which urges quick movement through rapidly changing situations. The beverage market is ever-evolving, and while tradition holds value, failing to adapt means losing relevance. A great example is canned Sikhye, which transformed a home-brewed drink into a convenient product.

Traditional beverages must embrace convenience, such as repackaging Jeho-tang—a historic summer cooling drink—as an energy drink, or positioning herbal teas as coffee alternatives.

The third key element is Heavy Ground, referring to crucial strategic positions. Traditional beverages, known for their natural and health-boosting ingredients, could carve out new niches by aligning with modern wellness trends, focusing on immune support, beauty benefits, or fatigue recovery.

Finally, Death Ground signifies a desperate situation where survival requires drastic action. If traditional beverages do not innovate, they risk disappearing entirely.

By incorporating them into the K-Food trend and reinterpreting them for modern markets, a new era for these drinks may yet unfold.

|

| ▲ Sikhye introduced as "Korean rice punch." YouTube screenshot. (PHOTO NOT FOR SALE) (Yonhap) |

(C) Yonhap News Agency. All Rights Reserved

![[풀영상] 2025 MBC 방송연예대상 레드카펫|유재석·전현무·기안84·김연경·세븐틴 부승관·박지현·제베원(ZB1) 규빈·투어스(TWS) 도훈·주우재·하하 외](/news/data/20251229/p179586605817354_616_h.jpg)