◇ Finally, to the Dream Lake Baikal

The journey to Baikal, that legendary body of water often mistaken for a "sea," began in earnest. Departing from the riverside city of Irkutsk, we traced the source of the Angara River upstream for 400 kilometers toward our destination, the majestic Lake Baikal.

The route was a mix of paved and unpaved roads, making the journey arduous. Even with the finest Korean-made buses, the trip took over seven hours. Along the way, the landscape unfolded into an unbroken expanse of grasslands.

For the first time in my life, I witnessed land so vast and limitless that the horizon seemed like a mysterious, unreachable frontier. Traversing such an expanse by foot would have been inconceivable in the past; only swift horses could transport travelers across these boundless plains.

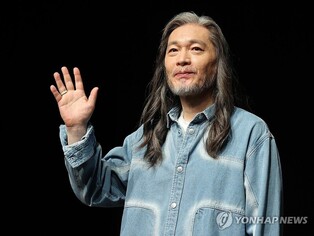

During the monotonous hours, Dr. Lee In-ho, a former ambassador to Russia and an eminent historian, delivered an unforgettable lecture. Unbothered by the many passengers who appeared lost in sleep or private thoughts, the professor recounted the sweeping history of this immense land, from late Imperial Russia through the Bolshevik Revolution to the formation of the Soviet Union. His unwavering dedication made this part of the Baikal journey a standout experience.

|

| ▲ Angara River, observed from above Irkutsk, Russia, on July 20, 2015 (local time), glows with a blue hue. (Yonhap) |

◇ The Sacred Sea of Siberia

Situated in the southernmost part of Siberia, Baikal is still a northern frontier by our standards, spanning latitudes 51°N to 55°N. It holds one-fifth of the Earth's freshwater. With a maximum depth of 1,637 meters, it is the deepest lake in the world.

Baikal stretches 636 kilometers in length and up to 80 kilometers in width at its broadest point, narrowing to 27 kilometers at its slimmest. Its average width is about 48 kilometers, giving it an expansive reach that truly feels like a sea. Geologically ancient, over 500 million years old, it is composed of metamorphic, sedimentary, and igneous rocks. The lake's primeval aura is matched by its unique and diverse ecosystem.

◇ A Treasure Trove of Biodiversity

Baikal is home to over 1,200 species of animals and 600 species of plants, with 75% of them being endemic. Its native fauna includes whitefish, sturgeon, and the remarkable Baikal seal, or nerpa, the world’s only freshwater seal. The nerpa's lineage traces back to an era when the lake was part of an ocean, surviving the transition to freshwater.

The Buryat Mongols call Baikal "rich waters," a name that aptly reflects its unparalleled purity and abundance. Known by various epithets—"Sacred Sea," "Blue Eye of Siberia," "Oasis of the Earth," "God's Sacred Gift," and "Ecological Treasure Chest"—it was designated a UNESCO World Natural Heritage Site in 1996.

Baikal is not merely a lake; it is a repository of natural wonder, history, and reverence—a destination that transcends its physical beauty to evoke awe and inspiration.

As we traveled, we passed by scattered wooden poles and totems along the roadside—symbols resembling Korea's sotdae and jangseung. Though their designs differed slightly, their meanings were identical. The rituals performed here—tying cloth to make wishes, offering sacrifices, and pouring alcohol—closely mirrored our traditions.

The only difference was the choice of offerings: instead of Korean makgeolli or soju, they poured vodka, adding a distinctly Western flair. Remarkably, cigarettes and coins were also placed on these altars as part of wish-making. Shamanism, with its belief in spirits residing in all things, endows the world with thousands of deities.

This worldview acknowledges both benevolent spirits of the heavens and malevolent forces of the underworld, requiring prayers even to dark spirits under certain circumstances. While shamanism may seem primitive for this reliance on countless spirits and devils, it felt familiar, echoing the practices of Korean shamans who mediate between humans and the divine.

Historically, these heavenly spirits were called Tengri. As noted earlier, Choi Nam-seon believed that the word Tengri served as the etymological root of Dangun and that the Korean word for shaman, danguri, derived from this term as well.

I was reminded of another intriguing book I had read years ago, though I couldn’t recall its exact title—something about the origins of the petroglyphs at Bangudae. That book traced the migration path of similar petroglyph styles and concluded that they converged at Buryatia and Lake Baikal. While I largely agreed with the theory, I found its explanation lacking on why these ancient peoples would traverse the formidable Altai Mountains to move southward.

|

| ▲ The "80th Anniversary of the Forced Relocation of Koreans" exploration team observes Lake Baikal on July 29, 2017. The lake boasts remarkable transparency, allowing visibility up to 40 meters below the surface. (Yonhap) |

◇ Arrival at Baikal’s Shore

After passing the villages of Bayandai and Elantsy, we finally reached the ferry terminal to Olkhon Island after seven long hours. About five minutes before arriving, Lake Baikal’s vast, shimmering surface began to emerge beyond the rolling grassy hills.

Disembarking from the bus, we stood at the water’s edge, beholding the famously clear waters of Baikal. The lakebed was fully visible, confirming its reputation as the clearest water on Earth.

Though Baikal holds one-fifth of the planet's freshwater, it maintains its unparalleled purity through a remarkable, almost mystical self-purification process. At depths of 30–50 meters below the surface, the water is so clean it can be scooped directly as drinking water—purer than any glacial melt or bottled spring water.

The bottled water I had sipped the day before carried the label Legend of Baikal. As with a fine wine, I carefully peeled off the label, preserving it as a memento of this extraordinary encounter with the sacred waters of the world's deepest and most pristine lake.

As we waited for the ferry, some people took to the water for a swim, while on the opposite shore, others were busy smoking omul (scientific name: Coregonus autumnalis), a fish that is a staple of the region. Similar in shape and size to sardines, omul is a fatty fish native to Baikal. The fish is gutted, salted, and smoked over birch wood on an iron grill, and it is eaten fresh, torn apart by hand right there on the spot.

I had tasted omul sashimi in a restaurant earlier, and though it was acceptable, it didn’t seem to be an everyday dish for the locals. The ferry we were boarding was a unique vessel, similar in shape to a barge, originally used by the Russian navy. It was large enough to carry a bus and operated on a free schedule by the local government, with ferries departing every 15 minutes. Departure and arrival times were rather unpredictable, dependent on the availability of the crew, many of whom wore military reserve uniforms.

After about a 10-minute journey across a narrow strait, the ferry arrived at Olkhon Island, known as the "navel of Baikal."

|

| ▲ This image of roasted arctic cisco is captured from Wikipedia. (PHOTO NOT FOR SALE) (Yonhap) |

◇ Olkhon Island

Disembarking at the ferry terminal, we continued on an hour-long bus ride along a dusty, unpaved road towards the island's main settlement, Khuzhir. The name Olkhon translates to "dry" or "treeless," which is fitting for an island that stretches 72 kilometers from north to south and 15 kilometers from east to west. Though not small, the island's population is under 1,500, most of whom live in Khuzhir.

The majority of the island’s inhabitants belong to the Buryat ethnic group. Their appearance closely resembles that of Koreans, and their children, in particular, could easily be mistaken for Korean children. This similarity has led some to consider Olkhon as the ancestral homeland of the Buryat people. The island is also the setting of a legendary myth about Khori-doi, the ancestor of the Buryats, who is said to have hidden the wings of a swan on this very island.

According to legend, several Baikal deities once gathered to live on Olkhon Island. Among them was Khanhute Babaai, a white eagle-shaped deity, whose son, Khansuub-Noyon, was the first to receive the power of a shaman from Tengri, the sky god. Because of this, Olkhon is regarded as a sacred place for shamans. During the time of Genghis Khan’s conquests, many shamans who faced persecution by Lamaism sought refuge on the island, and it has since become the site of the annual World Shaman Festival.

The village of Khuzhir itself has a rustic charm, with log cabins lining the expansive, barren plains, much like a Western frontier town. Some of the cabins are old, while others are newer guesthouses. These log homes are known as turbažals. At dinner, we were served traditional Russian soup, bread, smoked omul, and a bilmin, a dumpling soup that was quite satisfying.

Next, we were served shashlik, a skewered pork barbecue. Once again, the smoky scent of birch wood filled the air. It was the perfect pairing with vodka, though here, vodka isn't served ice-cold—there’s no refrigeration available.

The cold beer was a pleasant contrast, and sipping the lukewarm vodka while enjoying the chilled beer as a "chaser" was an unbeatable combination for getting tipsy. The final touch was a hot cup of black tea, which helped to ease the lingering effects of the alcohol.

|

| ▲ This image of the Baikal is provided by Hanatour. (PHOTO NOT FOR SALE) (Yonhap) |

The accommodations on Olkhon Island were quite rustic, with separate outdoor toilets much like those in old country houses. The latrine was deep and large enough to be intimidating, but fortunately, the hole in the ground was small enough to prevent any serious mishaps. Concerned about snoring, I requested a private room, but the partition was flimsy, and my roommate complained of being repeatedly woken up by my snoring.

It wasn’t so much the noise from the passing Soviet-era tank that disturbed him, but the eerie silence that would fall for a long moment before the snoring started again. It was this unsettling quiet that made him uneasy.

I, too, had a restless night, waking up and falling back asleep repeatedly, mostly because of the terrifying mosquitoes. Mosquitoes are the scariest creatures to me—they’re the smallest beings but seem to target me exclusively, and the itching they cause is unbearable. I brought all sorts of mosquito repellents: sprays, creams, patches, and sticks—all of which proved futile. It seemed every mosquito on the island had an unshakable attraction to me.

Still, there was something I was grateful for: despite the mosquitoes and the need to get up to relieve myself, each time I woke, I was greeted by a refreshing burst of fresh air that filled my nostrils with an almost sweet flavor. It was a strange and delightful sensation to feel that each breath of air tasted so sweet. If life were lived that way—every breath taken with the flavor of sweetness—it would be an entirely different experience.

And every time I walked across the yard to the toilet, the sky above me would be filled with stars, as if hosting a night-long party. Among them, some stars would break away in brief streaks, falling like shooting stars. In just a short time, I could count more than ten falling stars.

I remembered that if you make a wish when you see one, it’s supposed to come true. With so many falling stars in the sky, it felt as though wishes were being granted right and left—surely something that could only happen in heaven.

(C) Yonhap News Agency. All Rights Reserved