*Editor’s note: K-VIBE invites experts from various K-culture sectors to share their extraordinary discovery about the Korean culture.

Choi Man-soon's Medicinal K-Food: From War Strategies to Savory Pancakes

By Choi Man-soon, Food Columnist and Director of the Korea Traditional Medicine Food Research Institute

"Without money, why not fry up some mung bean pancakes at a tavern?

Why is a broke scoundrel going to a fancy restaurant?"

These are lyrics from singer Han Bok-nam’s 1943 hit "Gentleman Eating Mung Bean Pancakes." The song, remade by many singers over the years, remains a timeless anthem. Recently, it was reimagined as a retro swing track by K-Oppa, An Seong-jun, Lee Ye-jun, and Seong Jin-woo on MBC’s "Trot’s Nation."

The song humorously depicts a "gentleman" who has squandered his inheritance, now left with just one suit, attempting to dine-and-dash at an expensive restaurant only to get caught and beaten. The curious line, “If you’re broke, just eat mung bean pancakes,” highlights the comforting role this dish has played in Korean life.

|

| ▲ Bindaetteok and Makgeolli. (Yonhap) |

Mung bean pancakes, or bindaetteok, have long been a symbol of warmth and solace, evoking the desire to pause and savor life amidst the daily grind. Their aroma is more than a nutty scent; it melts away life’s weariness and stirs nostalgic longings for home.

For me, the smell of bindaetteok brings back vivid memories of winter days in my childhood. My mother, predicting snow, would wake early to soak mung beans in water. Sure enough, by mid-morning, snowflakes would blanket the ground. By then, she would have washed and peeled the mung beans, draining them in a sieve before grinding them in a millstone—an essential kitchen tool in every home before blenders became common.

The ground mung beans would be mixed with a touch of flour, kimchi, scallions, minced pork, and seasoned with salted shrimp, a vital winter ingredient at the time. She would heat a skillet over glowing embers from the kitchen hearth, coat it with pork fat, and ladle the batter onto the pan. The tantalizing aroma would waft through the air, often drawing in neighbors who’d gather for a warm snack and conversation.

Sitting together, sharing stories over freshly fried bindaetteok, those moments remain etched in my memory. Over time, mung bean pancakes, alongside kimchi and bulgogi, have become a hallmark of Korean cuisine, even gaining favor among foreign visitors.

|

| ▲ Ahead of the Chuseok Holiday, vendors at a bindaetteok shop in Gwangjang Market, Yeji-dong, Jongno-gu, Seoul, on September 19, 2010, busily prepare for customers. (Yonhap) |

Interestingly, the process of making bindaetteok bears a resemblance to principles in The Art of War by Sun Tzu, particularly in the chapter on strategic attack. Sun Tzu emphasizes the importance of optimizing resources to achieve victory. Similarly, crafting the perfect bindaetteok involves efficient and resourceful steps to yield a delightful outcome.

The idea of "winning efficiently" aligns with the philosophy of bindaetteok. Sun Tzu advises against prolonged conflicts, which are detrimental to all parties, advocating for swift and decisive strategies. In its simplicity and ingenuity, bindaetteok embodies this principle—a humble dish that turns limited resources into something truly satisfying.

When frying mung bean pancakes (nokdu bindaetteok), overcooking can cause the oil to soak in, making them greasy. Prolonged cooking diminishes the flavor and benefits of the ingredients, so it’s ideal to remove the pancake when the edges turn golden brown.

In The Art of War, Sun Tzu emphasizes the importance of a leader being wise and decisive in the section on “The Role of the Commander.” The cook making bindaetteok assumes this leadership role, balancing every aspect—ingredient ratios, griddle temperature, and cooking time—ensuring the perfect pancake.

Mung beans originate from India and Myanmar and have been cultivated in Korea for over 2,000 years. They are resilient to drought and have a shorter growing period than soybeans or red beans, making them well-suited to late planting. In Korea, sprouted mung beans are widely enjoyed as sukju namul.

In traditional Korean medicine, mung beans are described as sweet, non-toxic, and cooling in nature. Peeled mung beans are considered neutral in their properties. They help clear internal heat, detoxify, and alleviate symptoms such as burning skin, heat-induced thirst, swelling caused by internal dampness, and boils caused by stagnant energy and blood.

|

| ▲ Making Bindaetteok (Korean Mung Bean Pancakes). (Yonhap) |

Additionally, the nutrients in mung bean powder are noted for their ability to lower lipid levels, regulate cholesterol, prevent arteriosclerosis, and protect the lungs and liver. They are also said to support kidney function and improve bowel and urinary health.

Mung bean pancakes originated in regions like Hwanghae and Pyeongan provinces and gradually spread nationwide, developing regional variations and becoming a popular dish. They were often made to serve guests and were also distributed by wealthy families to the poor during times of famine.

In Korea, bindaetteok ingredients can be categorized into two main types: mung beans and buckwheat. The preparation and ingredients for both are similar, involving ground beans or grains mixed with minced meat, kimchi, and vegetables, then fried in oil.

While their benefits overlap, buckwheat stands out for its ability to dissolve blood clots, regulate blood pressure, and aid in weight management. Ancient texts even caution, “Frequent consumption of buckwheat can lead to weight loss, so be mindful.”

As for mung beans, Li Shizhen, the author of the Compendium of Materia Medica, reportedly suffered from frequent eye infections in his youth due to his love for pepper. He found that mixing pepper with mung beans eliminated his eye problems, underscoring their detoxifying properties.

|

| ▲ On the night of February 5, 2010, the last day of operation for Cheongiljip—the oldest establishment in Seoul’s Pimatgol area, first opened after Korea’s liberation in 1945—owner Lim Young-shim (61) diligently makes bindaetteok. (Yonhap) |

The name bindaetteok is believed to have evolved over time from "byeongjabyeong" (餠子餠) to "binjatteok," and eventually to its current form.

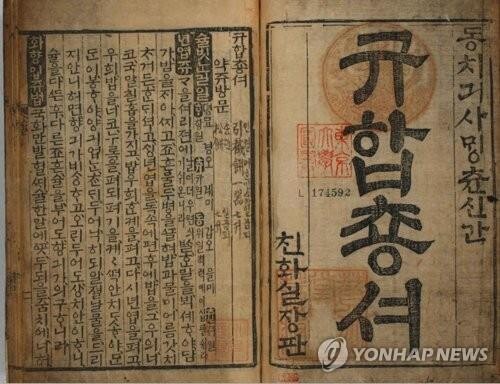

There are numerous theories regarding the origin of bindaetteok. The dish first appeared in literature as "binjabeop" in Eumsikdimibang. Later, in Gyuhapchongseo, it was called "byeongja," and in Joseon Musang Sinshik Yori Jebeop, it finally appeared as "bindaetteok."

In Joseon Sangshik, it is suggested that the term binjatteok might derive from the Chinese term "bingjing" (餠飣). Similarly, Choe Se-jin's Bak Tongsa Eonhae, which transliterates Chinese into Korean pronunciation, also notes that bindaetteok originated from the Chinese pronunciation of the word. Another theory posits that bindaetteok came from the term "bin-dae" (賓待), meaning "guest reception," as mung beans were once scarce, and the dish was prepared as a special treat for guests.

Originally, bindaetteok was used as a base for stacking fried meat on ancestral or ceremonial tables. At the time, the pancakes were smaller in size. Recipes for bindaetteok from various sources provide fascinating details.

In Gyugon Siuibang, the method is described as follows: "Peel mung beans, grind them into a thick batter, and place small portions on a griddle once the oil is hot. Add a filling made of peeled mung beans mixed with honey, cover with more batter, and fry."

The Gyuhapchongseo adds more detail: "Grind mung beans to a thick consistency. Add enough oil to cover the griddle, then spoon mung bean batter onto it. Place a filling of sweetened chestnut paste mixed with honey, cover with more batter, and press evenly with a spoon to create a decorative floral pattern. Garnish with pine nuts and jujubes before frying." This version of bindaetteok resembled a hwajeon-style pancake more than the modern version.

|

| ▲ Gyuhap Chongseo. (Yonhap) |

Joseon Musang Sinshik Yori Jebeop offers a similar recipe: "Peel mung beans, soak them with glutinous rice, grind them with water, then mix with beaten eggs and fry like pancakes." The recipe emphasizes that using ample oil and eggs enhances the flavor and texture of the dish.

Caution is advised when grinding mung beans or frying pancakes: the beans should not come into contact with brass utensils, as this could cause spoilage. Wooden or earthenware containers are recommended. Mung beans must be ground and fried simultaneously to prevent fermentation, and small portions should be spread thinly and fried immediately.

This cookbook also provides instructions for creating bindaetteok with alternative fillings, making it particularly noteworthy. The fillings could include parboiled green onions, water parsley, or napa cabbage stems, alongside minced and seasoned beef, chicken, or pork. Additional ingredients like rehydrated sea cucumbers and abalones, shredded red pepper, pine nuts, raw chestnuts, jujube slices, and hard-boiled eggs could also be included. All these fillings were combined and fried into pancakes, then served with a dipping sauce.

Some variations even included red pepper powder, illustrating the incredible diversity of ingredients and preparation methods for bindaetteok.

The Joseon Musang Sinshik Yori Jebeop also includes a recipe for kimchi bindaetteok: "Soak mung beans in water overnight, then wash them repeatedly to remove the skins and any remaining grit. Grind them thickly with a millstone. Cut water parsley into one-inch pieces, mix with mung bean batter, and season with salt. Grease a griddle and fry the batter into thin pancakes, roughly the size of a small plate. Additionally, grind mung beans in the same way, julienne napa cabbage kimchi, mix them together, grease the griddle, and fry."

This recipe bears a strong resemblance to the kimchi bindaetteok enjoyed today.

However, modern bindaetteok differs from earlier versions, which were often sweet, decorative, and fragrant "cakes" akin to the recipes described above. It no longer resembles a delicate jeonbyeong (pancake-like treat) but has become a savory, hearty dish.

Seasoned with salt and featuring a mix of meat and vegetables instead of sweet red bean paste, bindaetteok has become a popular everyday food. Its size is thought to have increased during times of famine or as a means of charitable provision for impoverished scholars, making it more substantial.

Today, bindaetteok is a favored accompaniment for alcoholic beverages. It is also believed to aid in the prevention of lifestyle diseases like hypertension and alleviate hangovers and fevers, making it a beloved dish among Koreans. Moreover, with the global rise of K-food's popularity, interest in bindaetteok is now spreading worldwide.

(C) Yonhap News Agency. All Rights Reserved

![[가요소식] 베이비몬스터, 첫 북미 투어 다큐 공개](/news/data/20260102/yna1065624915971209_797_h2.jpg)