Continuing from my previous column, here’s another piece from my journey to Pyongyang 20 years ago.

On the second day of my visit, after an afternoon of sightseeing, I boarded the car to head to dinner. My designated car had changed from Car 1 to Car 2, and the female guide in Car 2 took a seat next to me.

On the drive back to the hotel after dinner, our conversation naturally turned to religion.

"I don’t have a religion. I believe in the Supreme Leader and Juche ideology," she said with a composed and detached expression, which contrasted with her pretty face. She then quickly changed the topic.

"You’re fortunate, being an architect."

It seemed she knew quite a bit about me. Of course, she’d likely studied up on all the visitors beforehand.

"Fortunate, how so?"

She responded without hesitation, as if she’d prepared her answer.

"Doesn’t an architect’s work outlast his lifetime?"

It was a bold question.

"Well, yes... but that also means a lot of responsibility. If I make a mistake, that mistake will last just as long."

I wondered if she would understand what I meant, but I decided to keep it simple.

"If you stay true to your ideals and principles, there won’t be any mistakes, right? What’s your guiding principle?" she asked, undeterred.

Another bold question.

"I believe we must prioritize the environment. In the South, particularly in Seoul, environmental issues are very serious."

This answer left her looking a little puzzled for the first time.

"In our architecture, we combine socialist and nationalist elements to create a unique style," she replied.

Impressed, I quickly took out my notebook to jot down her words.

“You’re quite remarkable. When did you learn all of this?”

She responded thoughtfully. "I graduated from Kim Il-sung University with a degree in Korean literature," she said, but she had a surprisingly mature way of addressing the questions I had about the North.

"I actually wanted to study architecture at first."

At this point, I felt the need to change the topic. Otherwise, the entire ride might turn into a lecture on Juche ideology.

"You have a wonderful voice, comrade guide. Will you sing a song for me? Do you know A Person Who Remains in the Heart?"

The question seemed to catch her off guard, momentarily transforming her demeanor.

"Another guide is better at singing. She has a lark’s voice," she said, gesturing toward her colleague in the back.

“Oh, she can sing later. You first,” I replied playfully.

To my surprise, she stood up, walked to the front of the vehicle, and took hold of the microphone.

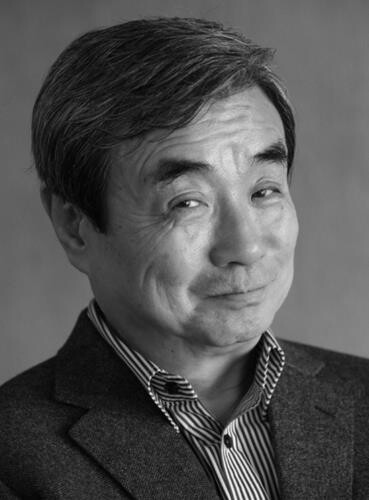

"In life’s journey, we encounter so many meetings and farewells. Even if we part ways, there are those who remain in our hearts. Ah, such a person I cannot forget. Some are with us for years yet leave no memory, while some we meet only briefly but stay in our hearts. Ah, such a person is precious to me."

The lyrics were simple, and the melody was straightforward, yet it struck me as remarkable that in North Korea, after the patriotic songs like Sea of Blood and Whistle, a love song like this now existed. She closed her eyes, singing two verses of A Person Who Remains in the Heart, then invited everyone to join her in a chorus three times.

"You sing so well, comrade. You could have had a successful career in music. And you’re the prettiest woman in Pyongyang, too."

Her face turned red. She tore a page from her notebook and wrote down the lyrics for me. As we arrived at the hotel and prepared to disembark, she said,

"Tomorrow, please consider switching to Car 2.”

|

| ▲ This image of the written lyrics of North Korean song "A Person Long in My Heart,"copied down by a North Korean guide, is provided by the author. (PHOTO NOT FOR SALE) (Yonhap) |

The Pyongyang Shoulder-to-Shoulder Children’s Hospital and Other Visits

The following morning marked the main event of our visit: the completion ceremony for the "Pyongyang Shoulder-to-Shoulder Children’s Hospital." The hospital, situated on the main street of Saesalim-dong in Dongdaewon District, spans about 1,300 pyeong (roughly 4,300 square meters) and stands out for its bright, well-designed structure. Thanks to dedicated efforts, including those of Chairman Kwon Geun-sul of the “South-North Children’s Shoulder-to-Shoulder Foundation” and doctors from Seoul National University Hospital, this building was finally brought to fruition.

Architect Hwang Young-hyun, who had collaborated on the project, shared his experiences, mentioning he’d traveled to Pyongyang nine times and endured many challenges, his emotions barely held back as he spoke. This two-story hospital is equipped with essential diagnostic tools, such as X-ray machines and ultrasounds, along with dental equipment—donations from Seoul National University Children’s Hospital. Many South Korean companies contributed as well, supplying finishing materials, fixtures, and lighting equipment.

Unexpectedly, the names of the donors, including mine, were inscribed on a large bronze plaque at the entrance. This was surprising, given North Korea’s tendency to keep such details from public view.

In previous years, several South Korean formula companies had sent powdered milk for North Korean children. However, as local children had difficulty digesting it, the idea arose to build a soybean milk factory adjacent to the hospital, which was completed along with the hospital. This factory now produces five tons of soybean milk daily, branded as "Baby's Milk," and supplies it to 3,500 children each day. Soybeans are easily cultivated on local farms, and North Korean children find them easier to digest, making this solution particularly practical.

One of the most notable aspects was that all the factory’s production equipment was provided by South Korea. Each machine was clearly marked with its origin, such as "Daegu XX Machinery Manufacturer," which was surprising. Later that evening, the event even received a detailed feature in the evening edition of Rodong Sinmun, North Korea’s official newspaper.

As someone who habitually keeps news clippings, I briefly considered taking a copy of the paper, but then dismissed the idea, thinking that the National Intelligence Service might interpret it as possession of "enemy material."

Following the ceremony, we bid farewell to the hospital staff and children, who sent us off with warm, enthusiastic goodbyes, and then we went to lunch at the Koryo Hotel, one of the top restaurants, equivalent to South Korea’s Shilla Hotel.

|

| ▲ This undated Yonhap file photo shows North Korean farms and agricultural fields. (Yonhap) |

Since arriving in Pyongyang, I’d been eating sumptuous meals, more than I could finish, each day. This excessive abundance made me question whether it was truly acceptable, especially considering the situation in North Korea.

After some thought, I came to a conclusion. Judging by international standards, the North had likely set the cost of food and accommodations at rates reflecting those standards. Still, living expenses here must be around a tenth of what they are back home, so paying more for what was provided might be a way to support the locals. With that logic in mind, I decided to fully enjoy the meals without overthinking it.

After lunch, our next stop, guided by the National Reconciliation Council, was Pyongyang’s Model Elementary School No. 4, a prestigious school attended by the late Kim Jong-il.

Their eagerness to show us as much as possible was both impressive and overwhelming. While I appreciated their hospitality, I couldn’t help but feel that some of their efforts aimed at subtly "educating" us.

This thought occurred to me because the elementary school appeared to operate almost exclusively for display. Nevertheless, since our group included 10 South Korean children, interactions between the children carried genuine significance.

Even so, the school’s musical and dance presentations felt overly rehearsed and meticulously organized, which made it difficult to connect with them. One couldn’t help but wonder why they didn’t recognize the counterproductive effect of this overly staged approach.

Student Youth Palace and Pyongyang’s Cultivated Talent System

The sense of unease reached its peak when we visited the Student Youth Palace. In North Korean terms, this facility is where they identify young talent early and offer specialized training, akin to our concept of gifted education. Here, around 500 children gather after school, divided into 80 specialized groups (or "sujos") to receive intense instruction in various disciplines.

While I suspect these children likely come from select backgrounds, what we saw—groups practicing swimming, table tennis, taekwondo, piano, accordion, traditional Korean painting, and embroidery—revealed a remarkable degree of training. These children weren't engaging in after-school activities in a typical sense; instead, they had achieved an almost circus-like mastery through rigorous, repetitive drills.

Consider a six-year-old performing a flawless 10-meter dive, or a five-year-old executing rapid-fire table tennis rallies with astonishing precision—feats we applauded with mixed emotions. Do they realize that our applause doesn’t come from joy but from the unsettling feeling that this level of performance isn’t entirely innocent?

After we toured the individual sujos, we were escorted to a grand auditorium, large enough to seat 2,000 people. Under the watchful eye of a principal who bore a striking resemblance to Kim Il-sung (we all speculated he was likely a close relative of the Kim family), the children performed in a talent showcase. It was a truly professional performance, on par with world-class acts. The children were impressively talented, almost unnervingly so.

Yet, I couldn’t help but question the purpose of it all. Shouldn’t these children be running freely, eating and resting to their hearts’ content, and simply enjoying their childhood? Instead, here they were, executing well-rehearsed performances in a palace constructed for them—an elaborate structure adorned with marble.

I later learned that the building’s original design was rectilinear, but the "Leader" had intervened, insisting that the structure adopt a curved form, symbolizing a "loving embrace" for the children. The building, with its exaggerated scale and vast plaza, felt more like a ghostly temple for deities than a place for young children.

Later that night, after several refusals, I finally gave in to the persistent urging of Han Yong-oe, president of the Samsung Cultural Foundation, and joined the group for a drink at the hotel’s 47th-floor bar. One of the young North Korean guides, who always wore his Kim Il-sung badge, joined us for what turned into a drinking match.

Our North Korean guide tried his best to avoid downing his drinks, while we drank enthusiastically, almost competitively. These guides had all visited the South multiple times for various discussions and knew about our infamous "bomb shots" (a strong drink of soju and beer combined) and their intense effects. Their apprehension about our drinking culture was obvious.

Meanwhile, we found the local drinks—like Baekdu Mountain bilberry liquor and Geumgang Mountain stone mushroom liquor—delightful. The well-trained and graceful female servers also captivated us, and, amid the revelry, distinctions between South and North blurred as we all enjoyed the moment.

These young North Korean women were polite, quick-witted, and showed no hesitation in pouring drinks. Someone jokingly asked one of them, “Miss, did you happen to graduate from the Student Youth Palace?”

She replied, “No, I graduated from Kim Il-sung University.”

|

| ▲ A North Korean employee adjusts her high heel while chatting with a colleague as they prepare for a luncheon meeting between North and South Korean families at a hotel on Mount Kumgang on the North's east coast on Oct. 21, 2015. About 390 South Koreans arrived at the mountain resort to have face-to-face reunions with their North Korean kin, separated from them by the 1950-53 Korean War. It is the first such reunions in nearly 20 months. A second group of some 260 South Koreans will do the same for three days starting on Oct. 24. (Yonhap) |

It reminded me of how, back in Seoul, room salon workers would sometimes claim to have graduated from prestigious schools. But in this case, her claim of being a Kim Il-sung University graduate might very well have been genuine.

The saying "Southern men, Northern women," long familiar to the ear, has taken on real significance during my days here. It’s as if there’s been an unspoken “Miss Pyongyang” contest, where only the most beautiful women have been gathered.

If the North Korean women had access to the same advancements we have in the South—hair styling, cosmetics, plastic surgery, fashionable clothing, lingerie, as well as fitness regimens like dieting, aerobics, body sculpting, and even vocal training—then they might indeed win every competition. Moreover, the once-familiar high-toned, declamatory style of North Korean broadcasting voices seems to have softened slightly, making conversations with them more demure and flexible in tone.

Their speech, however, still has a certain rawness to it. True to their belief in the Juche ideology, they strictly adhere to using pure Korean words, which can sound unusual to South Korean ears. Interestingly, their approach isn’t entirely off the mark; after all, as some point out, we in the South often use foreign loanwords for half our vocabulary, creating a noticeable linguistic gap. Ordinary conversation with them sounds gentle enough, yet whenever the subject of the "Great Leader" or "Dear Leader" arises, their tone shifts to a strikingly reverent pitch, which feels somewhat out of place.

Their vocabulary choice is equally distinct: everyday language is peppered with native Korean words, but when it comes to referring to their leaders, they seem to purposefully select complex Sino-Korean terms. Words like cheonchuljanggun (heaven-sent general), gyeolsauongwi (death-defying protection), seongunjeongchi (military-first policy), and hyeonjijido (on-the-spot guidance) make me wonder if the intention is to obscure meaning with sophisticated language, lending an air of grandeur to these terms.

One server, upon seeing a picture I’d taken of her, blushed and said, “It’s lovely.” The word gopda ("lovely") is a beautiful Korean word we seldom use in the South. It was a simple moment but a reminder of how deeply ingrained language and cultural nuances can be, even in the smallest of interactions.

Exploring North Korea's "Jangmadang" Market Economy

On the fifth and final morning of our stay in Pyongyang, we toured Kim Il Sung University. In North Korea, schedules are always subject to change, with no official itinerary distributed in advance or shared on printed A4 sheets like ours. Still, we were unexpectedly invited to visit this renowned university, which was a pleasant surprise.

However, this visit was yet another instance of the state’s usual propaganda tactics. The two hours allocated were primarily dedicated to materials highlighting Kim Jong Il’s academic achievements—his dedication, self-sacrifice, leadership, and foresight. These materials dominated our visit, which felt more like a lesson in ideology than an exploration of a higher learning institution.

One of our group requested a visit to the university library, only to be told there wasn’t enough time. Instead, they proposed a drive around the campus in our bus, a suggestion presented almost as a favor to us.

After returning to the hotel for a final lunch buffet, we were given a couple of hours to shop at a state-run department store before heading to the airport. Although few items were particularly enticing, many of us found ourselves browsing more closely and purchasing gifts as thoughts turned to family and friends in Seoul.

The store's female attendants were highly motivated, likely due to the incentive-based system implemented. Some even employed mild sales tactics. For example, they often claimed they had no small change for transactions in euros or dollars, subtly encouraging customers to add items to round up the amount. Others suggested purchasing extra items, pairing their suggestions with charming smiles and polite gestures, making it hard for anyone to decline.

These simple tactics were easy to notice, yet they struck me as endearing rather than deceptive.

It’s well known that North Korea’s economy struggled for a long time. This eventually led to the “July 1 Economic Management Improvement Measures” in 2002. These changes effectively meant the end of the ration system, the introduction of a market economy, and incentive-based wages in various sectors. Ending rations in a socialist state marked a monumental shift—essentially a declaration for citizens to fend for themselves by growing and selling vegetables in their courtyards or bringing produce to market to earn money. This was nothing short of a groundbreaking transformation.

Two years after these measures, we could see some signs of change. Street vendors sold vegetables, ice cream, and fruits from mobile stalls, and service industries such as dining, beauty salons, and barber shops became visible on city streets. The variety and prices of alcohol displayed in shops suggested these items weren’t exclusively for tourists.

At that time, a "son jeonhwa" (mobile phone) cost as much as $2,000, and approximately 2,000 units were reportedly in use throughout Pyongyang. "Saek television" (color TVs) were priced at $500, and computers at $1,000—expensive, but theoretically attainable.

There were even reports that some North Koreans were moving to smaller state-provided homes to save on living expenses, investing the savings in small-scale business ventures. The government appeared to tacitly allow such activities. It seems the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea had crossed a point of no return on its path toward economic liberalization.

Burning Bean Stalks to Boil Beans?

It was five in the afternoon, and we were back at Pyongyang's Sunan Airport. Standing on the vast tarmac alone was Korean Air flight 816 (our inbound flight had been 815), a Boeing 767 waiting to take us back to Seoul.

As I looked at the plane, I couldn't help but wonder how much longer it would take for flights like this to become a regular service—one of several that would run freely each day, much like flights to Busan, Gwangju, or Daegu. When will this become routine, carrying passengers between Seoul and Pyongyang without special arrangements or restrictions?

The name "Sunan" conjures thoughts of peace and comfort, a simple and harmonious term. And yet, how far from reality that seems.

Burning bean stalks to boil beans,

The beans weep within the cauldron.

Though they came from the same root,

How can their resentment be so harsh?

This sorrowful passage was reportedly recalled by the historian Shin Chae-ho, inspired by his reflections on Korean history. The lines, heavy with the grief of division, resonate deeply as one gazes out over the airfield, where the hope of unity feels both near and distant.

(To be continued)

(C) Yonhap News Agency. All Rights Reserved