*Editor’s note: K-VIBE invites experts from various K-culture sectors to share their extraordinary discovery about the Korean culture.

Choi Man-soon's Medicinal K-Food: Aesthetics of Tteokbokki As Korean Traditional Meal

By Choi Man-soon, Food Columnist and Director of the Korea Traditional Medicine Food Research Institute

Tteokbokki, a beloved Korean dish, embodies the essence of a traditional Korean meal setting, known as hansang charim (traditional dining table setup). Korean meals have long been centered around a harmonious mix of rice, the main staple, with various side dishes prepared from vegetables, meat, and seafood in diverse methods. Alongside these dishes, a soup or stew is typically served, with additional side dishes added based on one’s resources and preferences.

Tteokbokki simplifies this traditional meal into a single, easily accessible dish, combining all elements in one bowl that can even be enjoyed on the street. This savory dish is seasoned with an array of ingredients, including gochujang (Korean chili paste), soy sauce, sugar, green onions, garlic, sesame seeds, sesame oil, pepper, and red pepper powder, which are added to taste and for their health benefits. These seasonings not only enhance the inherent flavors and health properties of the ingredients but also add depth and richness to the dish’s taste. The primary ingredient, garaetteok (cylindrical rice cake), symbolizes health and longevity due to its long, round shape.

|

| ▲ Tteokbokki from Busan PIFF Square. (Yonhap) |

Recalling childhood memories, I vividly remember accompanying my mother to the rice mill a few days before the Lunar New Year to make rice cakes. We brought soaked rice, prepared in a woven basket from the previous night, to a bustling mill where the entire village would line up at dawn to prepare their rice cakes. The interior was filled with white steam, and a massive diesel engine clanked rhythmically like a steam locomotive, powering the machinery.

When our turn came, the mill owner mixed salt into the rice flour, steamed it, and then pressed it through a machine to produce a continuous stream of garaetteok, which was then cut and placed in water. The hot rice cakes, glistening with sesame oil, were packed into baskets, and the taste of freshly made garaetteok—steamy and warm—was heavenly, melting away the winter chill.

◇ The Art of Flavorful Combination in Tteokbokki

In The Art of War, Sun Tzu emphasizes the critical role of resources in successful military operations. Just as an army relies not only on the soldiers’ strength but also on resources like food, weapons, and supplies, effective resource management is essential for success. Food preparation similarly requires an efficient combination of ingredients, maximizing flavor and health benefits by blending various seasonings based on occasion, season, and preference.

The exact origin of rice cakes (tteok) in Korea is unclear, but their history likely dates back to the beginnings of agriculture. White cylindrical rice cakes (garaetteok) have been part of Korean cuisine since the Three Kingdoms period, and during the Goryeo Dynasty, the promotion of agriculture led to increased grain production, expanding the culture of rice consumption and rice cake-making. Additionally, Goryeo’s Buddhist principles encouraged moderation in meat consumption, further developing rice cake traditions.

|

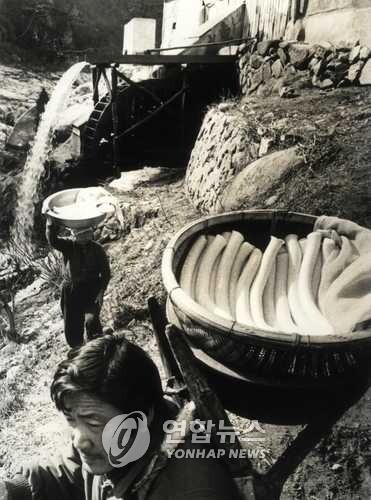

| ▲ This undated Yonhap file photo shows Korean New Year’s Garaetteok at the Mill. (Yonhap) |

Though today’s mills quickly produce garaetteok, traditional methods involved steaming rice flour, pounding it with a wooden hammer to achieve a chewy texture, and then shaping it into long pieces. In royal cuisine, garaetteok was cut into 4–5 cm lengths, soaked briefly, and stir-fried with seasoned beef, sliced zucchini, blanched bean sprouts, sliced shiitake mushrooms, onions, and carrots.

This traditional tteokbokki, combining rice cake, vegetables, and beef, was not only flavorful but also revitalizing. The recipe book Siui Jeonseo describes making tteokbokki similar to other steamed dishes, where rice cakes are sliced and briefly stir-fried without thick sauces. Another 19th-century cookbook, Jusiksiui, mentions stir-frying sliced rice cakes with beef in a generous amount of oil.

Through its resourceful blend of ingredients and seasoning, tteokbokki has evolved into a staple dish that represents the practicality and depth of Korean culinary traditions.

|

| ▲ Gungjung (royal) Tteokbokki Tasting Event. (Yonhap) |

◇ The Secret Sauce of Tteokbokki: A Flavor Hidden Even from the Daughter-in-law

Modern gochujang tteokbokki originated from Ma Bok-rim (1921–2011), who popularized her recipe with the slogan, "Even the daughter-in-law doesn’t know the recipe." In 1953, she began selling this iconic street food near Seoul's Shindang-dong, following the covering of a stream outside Gwanghuimun. Initially, she used a sauce combining gochujang (red chili paste) with chunjang (black bean paste) cooked over a coal fire. In the 1970s, the neighborhood gained national attention when featured on MBC’s radio program “Lim Guk-hee’s Women’s Salon,” sparking a nationwide trend.

Today, tteokbokki has branched into a variety of types. The two main categories are gochujang tteokbokki, which is spicy, and ganjang tteokbokki, which uses soy sauce for a milder taste. Gochujang tteokbokki’s flavor is built with spicy chili paste, sugar for sweetness, and additional ingredients like ketchup, mustard, or pepper for unique twists.

|

| ▲ This image of Maboknim Tteokbokki is captured from Namuwiki. (PHOTO NOT FOR SALE) (Yonhap) |

Rice cakes for tteokbokki are primarily made with rice flour or wheat flour, leading to two types: “rice tteokbokki” and “wheat tteokbokki.” During the early days of tteokbokki, when wheat flour became more accessible after the Korean War, wheat-based rice cakes were common. Today, both wheat and rice-based tteokbokki remain popular, with wheat tteokbokki often yielding a thicker, stickier texture, while rice-based ones retain chewiness even after prolonged cooking. Some vendors even combine wheat and rice cakes for varied texture.

A distinct type is made with a blend of wheat and starch flour, creating a chewier texture. The endless variety of sauces allows for flavors like cheese, cream, black bean (jjajang), curry, and rose tteokbokki, which mixes milk, cream, and tomato sauce for a unique twist. These sauce variations result in an array of flavors and textures, expanding the culinary possibilities of tteokbokki.

The adaptability of tteokbokki’s basic ingredients—rice and wheat cakes—means they pair well with almost any seasoning, with no conflicting flavors. This versatility has transformed tteokbokki from a simple street food into a beloved dish with countless variations, each with its own unique taste profile.

|

| ▲ The K-Food Festival, hosted by Korea's Ministry of Agriculture, Food, and Rural Affairs, was held on November 27, 2015 (local time), at Zabeel Park in Dubai, United Arab Emirates (UAE). Foreign visitors stand in a long line to try tteokbokki. (Yonhap) |

◇ Medicinal Qualities of Rice and Wheat in Korean Culinary Arts

In traditional Korean medicinal cuisine (yakseon), rice is considered the leader of the “five grains.” It is slightly sweet and bitter, with a balanced and nontoxic nature. Viewed medicinally, rice strengthens the digestive system, improves vision, enhances complexion, harmonizes the organs, strengthens muscles and bones, quenches thirst, sharpens hearing, cools the body, supports lung health, and promotes blood circulation. Particularly in clinical applications, rice is beneficial for restoring vitality after illness and fortifying weak constitutions.

Wheat, meanwhile, has a cooling property and a sweet taste. It is known to boost energy, dispel heat, dissolve clotted blood, aid the organs, support intestinal health, and alleviate pain. Wheat is particularly effective for easing stress, relieving insomnia, and soothing discomfort related to heat and emotional distress.

Globally, tteokbokki has gained recognition as an iconic Korean street food, with recent trends toward premiumization and diversification as part of the “K-food” wave. Brands have capitalized on specialized recipes, transforming tteokbokki into a sought-after item beyond casual street fare. A notable moment for tteokbokki’s international appeal occurred in Texas, where Chris Shepherd, a renowned local chef, prepared over 1,000 servings of Korean-style gochujang tteokbokki at the NFL Houston Texans’ stadium, only to have it sell out before halftime.

With K-food’s growing popularity, tteokbokki exports reached record highs this year, and eateries worldwide are increasingly adding tteokbokki to their menus. Representing the warmth and communal spirit of a traditional Korean hansang meal, tteokbokki is now solidifying its place as a rising star in global K-food culture.

(C) Yonhap News Agency. All Rights Reserved